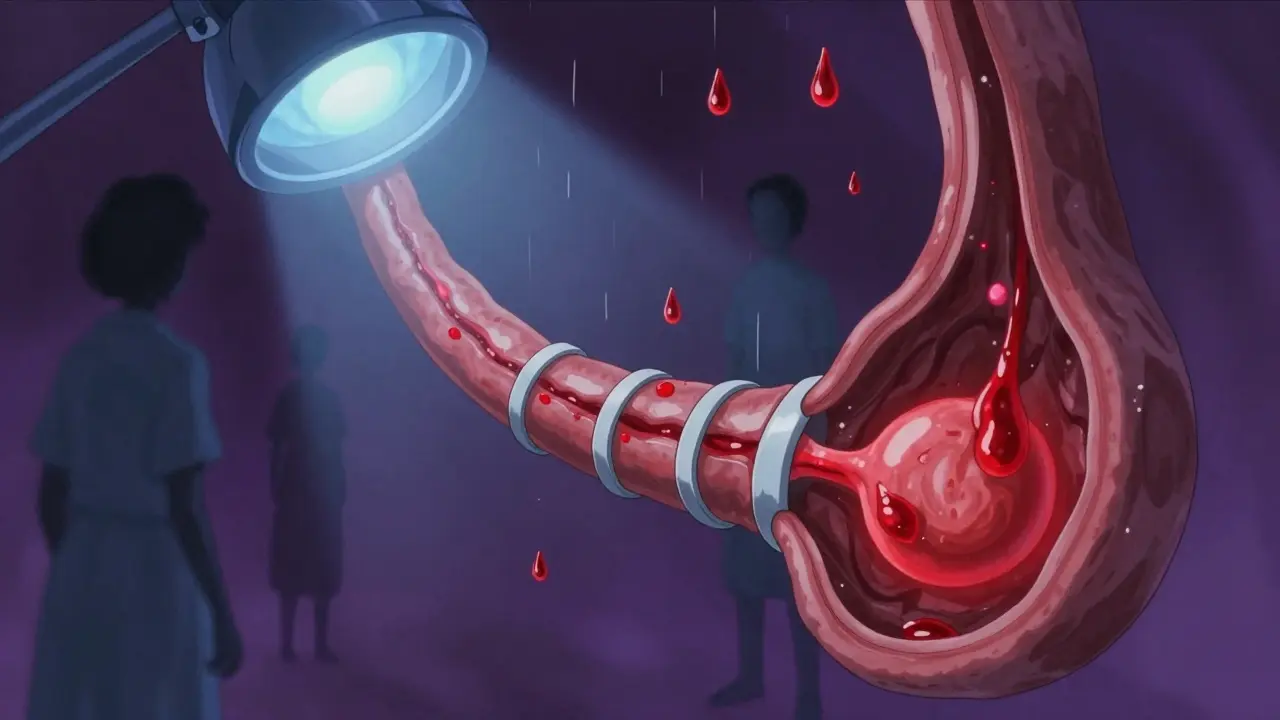

When your liver is damaged from years of alcohol use, hepatitis, or fatty liver disease, it doesn’t just slow down-it starts to block blood flow. That’s when pressure builds in the portal vein, the main vessel carrying blood from your gut to your liver. When that pressure hits 12 mmHg or higher, veins in your esophagus or stomach swell like overfilled balloons. These are varices. And when they burst, it’s not a minor bleed-it’s a medical emergency with a 1 in 5 chance of death within six weeks.

According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), about 250,000 people in the U.S. experience variceal bleeding each year. That’s more than the population of Birmingham, and nearly 20% won’t survive the first six weeks after the bleed. The key to survival? Speed. Treatment must begin within 12 hours of the first sign of bleeding.

Success rates? Between 90% and 95% for stopping the bleeding right away. That’s why EBL replaced older methods like sclerotherapy (injections of chemicals) in 2005. Modern multi-band devices, like the Boston Scientific Six-Shot system, can treat multiple veins in one go, cutting procedure time by 35% compared to older single-band tools.

But it’s not perfect. If the bleeding is heavy, the view gets blurry, and the procedure becomes harder. In those cases, banding fails in about 10-15% of patients. After the first session, you’ll usually need 3 to 4 more treatments, spaced 1 to 2 weeks apart, to fully eliminate the varices. Each session costs between $1,200 and $1,800 in the U.S., and while insurance covers most of it, out-of-pocket costs can still add up.

Side effects? Many patients report throat pain for up to two weeks. Swallowing feels like swallowing glass. But most agree: it’s better than the alternative. One patient on Reddit wrote, “Banding stopped my bleeding immediately. I was discharged in three days.” Another said, “I dread the appointments every two weeks-but I know it’s saving my life.”

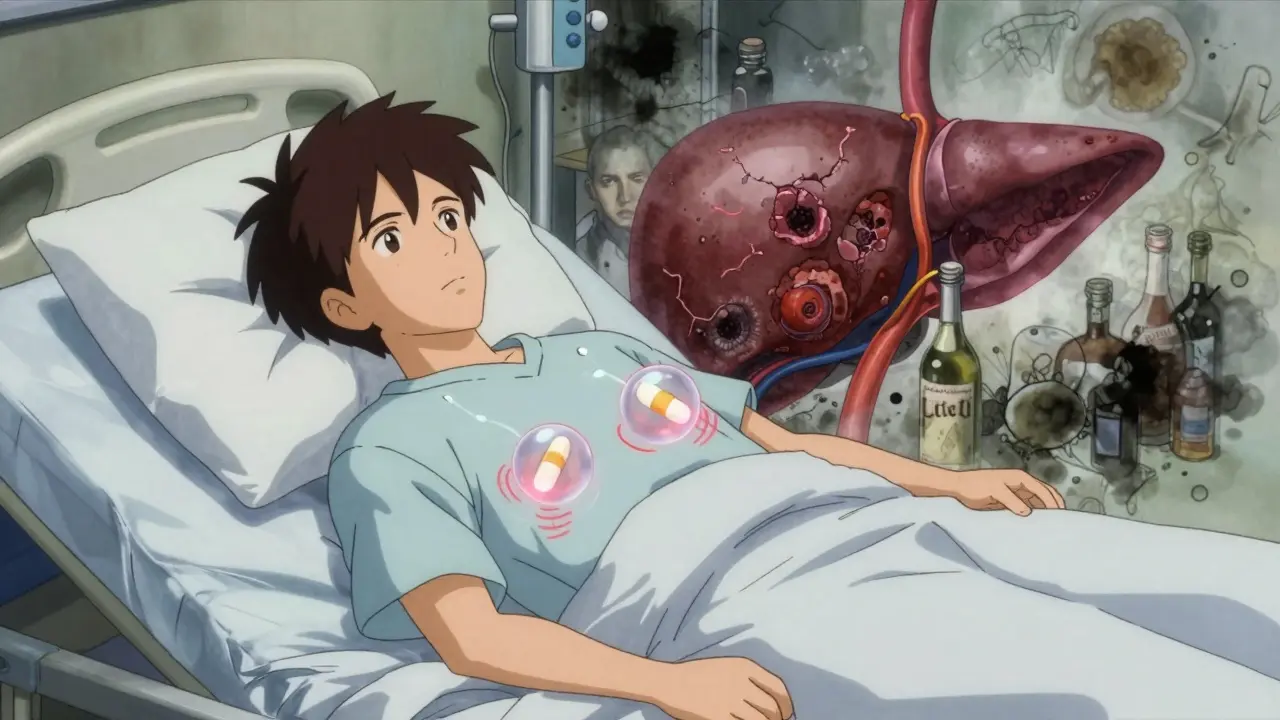

The two main ones are propranolol and carvedilol. Propranolol is cheap-$4 to $10 a month as a generic. Carvedilol is pricier at $25 to $40, but it works better. A 2021 study in Hepatology showed carvedilol lowers portal pressure by 22%, compared to 15% with propranolol. Both cut the risk of rebleeding by about half.

Here’s how they work: they slow your heart rate and reduce blood flow to your liver. Doctors monitor this using a test called HVPG (hepatic venous pressure gradient). The goal? Drop the pressure to 12 mmHg or lower, or reduce it by at least 20% from its original level.

But not everyone can take them. If you have asthma, a slow heart rate, or heart failure, beta-blockers can be dangerous. About 25-30% of patients can’t tolerate them because of fatigue, dizziness, or low blood pressure. One patient shared, “Propranolol made me so tired I couldn’t get out of bed. I switched to carvedilol-it worked better, but my copay is $35 a month.”

Importantly, beta-blockers alone won’t stop active bleeding. The Baveno VII guidelines from 2022 make this clear: pharmacological therapy alone only works in 50-60% of cases. That’s why you always get banding first, then beta-blockers.

One is TIPS-transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. It’s a tiny metal tube placed inside the liver to create a new path for blood to bypass the scarred area. It’s highly effective. A 2010 study showed patients with severe cirrhosis who got TIPS had an 86% one-year survival rate versus 61% with standard care.

But TIPS has a big downside: it can cause hepatic encephalopathy. That’s when toxins build up in the brain because the liver can’t filter them. About 30% of TIPS patients develop confusion, memory loss, or even coma. It’s a trade-off: save the bleeding, risk the brain.

Another option is BRTO (balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration), used mostly for stomach varices. It’s more effective than banding alone for those cases. A 2023 analysis showed 30-day mortality dropped from 6.2% with banding to 2.8% when BRTO was added.

But access is limited. Only 45% of U.S. hospitals have the trained interventional radiologists to do TIPS within 24 hours. That’s a major barrier. In rural areas or smaller hospitals, patients often get transferred-delaying treatment and increasing risk.

If you have cirrhosis but haven’t bled yet, your doctor should check for varices using an endoscopy. If they’re found and are large, you’ll be put on a beta-blocker-even if you’ve never bled. This is called primary prevention. Studies show it cuts the risk of first-time bleeding by 50%.

For those who’ve already bled, it’s called secondary prevention. You’ll get banding to remove the varices and beta-blockers to keep new ones from forming. This combo reduces rebleeding by up to 70%.

But prevention isn’t just about drugs and procedures. It’s about your liver. Stopping alcohol, managing hepatitis B or C, losing weight if you have fatty liver, and avoiding NSAIDs like ibuprofen can all slow cirrhosis progression. The American Liver Foundation estimates that 42% of patients struggle to stick with beta-blockers because of side effects-but even partial adherence reduces risk.

New developments are coming. In 2023, the FDA approved a monthly version of octreotide (Sandostatin LAR), which could help patients who can’t take daily pills. And in 2024, the Baveno VIII meeting will decide whether carvedilol alone can replace banding for primary prevention in high-risk patients.

Long-term, AI might help predict who’s about to bleed-before it happens. One expert predicts AI combined with new drugs could cut mortality by 40% in the next decade. But right now, disparities remain. Uninsured patients die at 35% higher rates than those with insurance.

What’s clear? Banding and beta-blockers are the foundation. They’re not glamorous, but they work. They’ve saved millions of lives. The challenge now is making sure everyone who needs them gets them-on time, affordably, and with the support they need to stick with treatment.

Band ligation works, but let’s be real-half the patients who survive the first bleed are just delaying the inevitable. Cirrhosis doesn’t care if your veins are tied off; your liver’s still a crumbling building with faulty plumbing. The real win is stopping alcohol before you ever get here.

Interesting breakdown-though I’d argue that the HVPG target of ≤12 mmHg or ≥20% reduction is oversimplified. In practice, the dynamic response to beta-blockers varies significantly based on hepatic vascular resistance, collateral flow patterns, and cardiac output modulation. Carvedilol’s alpha-1 blockade confers additional vasodilatory advantage over propranolol, particularly in high-resistance states. That said, adherence remains the Achilles’ heel-especially in populations with poor health literacy or socioeconomic constraints.

I’ve seen patients who refused banding because they were terrified of the scope. One woman said she’d rather die than go through it again. It’s heartbreaking. Sometimes the most life-saving treatment is also the most terrifying. Maybe we need more compassionate counseling before the procedure-not just clinical talking points.

Why are we still using 20-year-old protocols? The U.S. spends billions on banding while other countries use cheaper, equally effective methods. This isn’t medicine-it’s a profit-driven circus.

While the clinical efficacy of endoscopic band ligation and beta-blockade is well-documented, the socioeconomic determinants of access remain profoundly under-addressed. Rural populations, particularly in the American South and Midwest, face systemic barriers to timely intervention, resulting in disproportionate mortality. Policy reform must precede innovation.

Did you know the FDA approved octreotide LAR because Big Pharma wanted a monthly pill? They’ve been pushing this for years while hiding the fact that TIPS causes brain damage on purpose. It’s not about saving lives-it’s about keeping people dependent on treatments they can’t afford. The liver is a miracle organ, but the system? It’s broken.

Thank you for sharing this detailed overview. In India, we often rely on sclerotherapy due to cost and infrastructure limitations. While banding is superior, accessibility dictates practice. Many patients are lost to follow-up after initial treatment due to transportation and financial burdens. A global perspective is essential.

Let’s not romanticize banding. The 90% success rate is misleading-it only applies to controlled, early-stage bleeds. In real-world ERs, when the patient is vomiting blood and hypotensive, the endoscopist is lucky to get one band in before the field turns to soup. Most of these numbers come from academic centers. Community hospitals? They’re flying blind.

As someone who grew up in Nigeria and now works in a U.S. hospital, I’ve seen both sides. In Lagos, we use whatever we have-sometimes even balloon tamponade. Here, we have cutting-edge tech but patients still die because they can’t afford the copay. Medicine is universal. The system isn’t. We need to fix that.

It is imperative to recognize that the current paradigm of variceal management remains fundamentally reactive rather than proactive. The emphasis on secondary prevention, while clinically sound, fails to address the upstream etiological determinants of cirrhosis-namely, alcohol use disorder, viral hepatitis, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. A population-level public health intervention, including taxation, education, and screening programs, is not merely advisable-it is ethically obligatory.