NTI drugs - short for Narrow Therapeutic Index drugs - are medications where the difference between a safe dose and a harmful one is razor-thin. Take warfarin, for example. A little too much, and you risk dangerous bleeding. A little too little, and a blood clot could form. The same goes for levothyroxine, used for thyroid conditions: a small change in blood levels can throw your metabolism off, causing fatigue, weight gain, or even heart problems. These aren’t just any pills. They’re drugs that demand precision.

The FDA doesn’t publish an official list, but it’s clear which ones count: digoxin, lithium, phenytoin, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and theophylline are all on the radar. For these, the acceptable range for how much active ingredient is in each pill is tighter than for regular generics. While most generics must be within 80-125% of the brand-name drug’s potency, NTI generics must hit 90-111%, sometimes even 95-105%. That’s not a small tweak - it’s a stricter standard.

Here’s the problem: even if two generics meet FDA bioequivalence rules, they’re not identical. Different manufacturers use different fillers, coatings, and manufacturing processes. For most drugs, that doesn’t matter. For NTI drugs, it can.

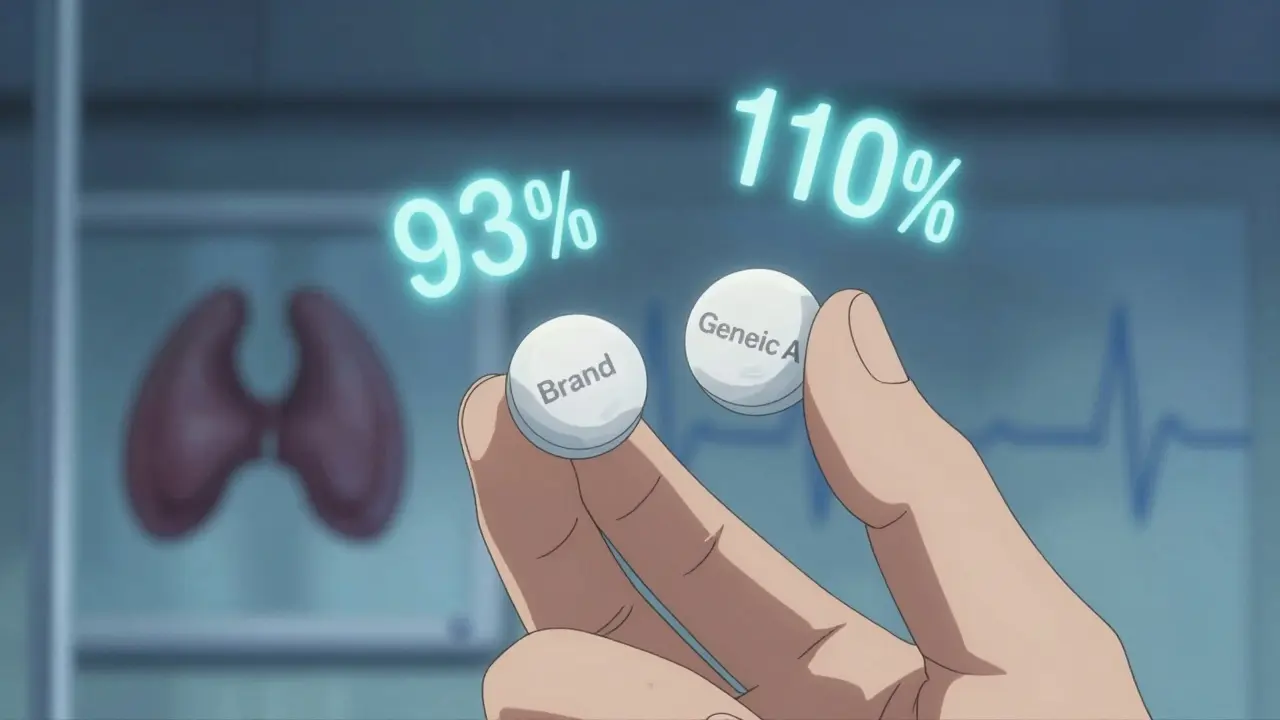

Take tacrolimus, used after organ transplants. A 2015 study found that when kidney transplant patients switched between generic versions, their blood levels varied by 21.9% on average. That’s not just noise - it’s enough to trigger organ rejection. One study compared four generic brands to the original brand. One version had 93% of the active ingredient, another had 110%. The FDA says that’s still within limits. But for a patient whose life depends on keeping levels steady, 110% might be too much, and 93% might be too little.

Same story with warfarin. A 2019 study showed that switching between generic manufacturers led to a small but statistically significant increase in INR variability - the measure of how well the blood is clotting. While major bleeding events didn’t spike, the fluctuations meant more doctor visits, more blood tests, and more stress for patients trying to stay in range.

On paper, the FDA says generic NTI drugs are therapeutically equivalent. And for many patients, they are. A 2021 FDA review of over 10,000 patients on generic levothyroxine found no meaningful difference in TSH levels compared to the brand-name version. The average TSH was 2.12 for Synthroid and 2.15 for generics - a difference too small to matter clinically.

But averages don’t tell the whole story. Some patients are sensitive. One study found that 63% of pharmacists had received complaints from patients or doctors after switching between generic brands of NTI drugs. That’s not a fluke. It’s real. A patient might do fine on one generic for months, then switch to another - and suddenly feel off. Their thyroid levels drift. Their seizures return. Their INR goes wild.

The American Academy of Neurology doesn’t trust the data enough to allow automatic substitution of antiepileptic NTI drugs like phenytoin and carbamazepine. Even though the FDA says they’re interchangeable, neurologists have seen too many cases where a switch led to breakthrough seizures. That’s why some states - 27 as of 2022 - have laws blocking automatic substitution for these drugs.

Pharmacists are trained to substitute generics to save money. But when it comes to NTI drugs, many hesitate. A 2019 survey found that 87% of pharmacists believe generic NTI drugs are just as effective as brand-name ones. Yet 82% said they almost always substitute generics for new prescriptions - meaning they’re doing it even when they’re unsure.

And here’s the catch: if a patient has a bad reaction after a switch, the blame often lands on the pharmacist. Even if the drug met all regulatory standards. The system doesn’t always account for individual biology. One person’s body might handle a change in filler perfectly. Another’s might not. There’s no test to predict who’s who.

Some pharmacists now ask patients: “Have you ever had a problem switching generics?” If the answer is yes, they avoid switching. Others stick to one generic brand for the same patient - and refuse to change unless the doctor specifically orders it.

If you’re taking an NTI drug, here’s what matters:

The FDA’s stance is logical: if a drug meets bioequivalence standards, it’s interchangeable. But biology isn’t a lab test. People aren’t averages. Some patients are like tuning forks - even a slight change in frequency throws them off.

One solution? Better tracking. Some hospitals now use electronic systems that flag NTI drugs and alert pharmacists not to switch without approval. Others maintain a “preferred generic” list for each patient. It’s not perfect, but it’s safer than letting the system make the call.

Until then, the safest approach is simple: consistency. If your drug is on the NTI list, don’t let it change unless you and your doctor agree. Your body isn’t a cost-saving experiment.

Oh wow, another ‘trust the FDA’ fairy tale 🙄 I’ve been on levothyroxine for 12 years and switched generics once-suddenly I was a zombie who couldn’t wake up. My TSH went from 1.8 to 7.2. Guess what? The pharmacy didn’t even tell me. #NotMyAverage

USA always overreacting. In India we switch generics daily and no one dies. If your body can’t handle a pill change then maybe you need better genes not better laws

I get it. But also… if your doctor doesn’t write ‘Do Not Substitute’ then you kinda asked for it. 🤷♂️

i just wanted to say thank you for writing this. i’m a nurse and i’ve seen so many older patients get confused when their pill changes color or shape. they don’t know what to ask. this info could save someone’s life 💙

Man… I had a cousin who was on tacrolimus after his transplant. Switched generics because insurance forced it. He ended up in ICU with acute rejection. They didn’t even realize it was the drug until his levels were checked. Now he’s stuck on the brand-name for life. And yeah, it costs $1200 a month. So… yeah. This isn’t just ‘cost-saving’. It’s life or death. 💔

so like if you take phenytoin and they switch you to a different generic and you have a seizure is that the pharmacists fault or the fda or the doctor or the insurance company

This is why African nations must not adopt American pharmaceutical policies. We have a functional generic system that prioritizes accessibility. The obsession with ‘precision’ is a luxury of the over-medicated West. Your body adapts. Stop whining.

i think we need more education for pharmacists and patients alike. i had no idea about ntis until my mom had a bad reaction. now we only use one brand and she’s doing great. maybe we can make a simple chart or poster in pharmacies? just a thought

LMAO at the 87% of pharmacists who think generics are fine but 82% still switch anyway. That’s not confidence. That’s denial with a side of paycheck.

Whatever. People die from bad diet, bad sleep, bad stress. Not from generic pills. Stop making this a thing.

I’ve been on warfarin for 8 years. Switched generics three times. Never had an issue. But I also get my INR checked every 2 weeks like clockwork. Maybe the problem isn’t the pill… it’s the lack of monitoring. Just saying.