When your liver fails, there’s no backup system. Unlike kidneys or lungs, the liver doesn’t have a reliable mechanical substitute. That’s why liver transplantation remains the only real chance for survival in end-stage liver disease. It’s not a simple fix-it’s a complex, life-altering journey that begins long before the operating room and lasts a lifetime after. If you or someone you care about is facing liver failure, understanding the steps-from who qualifies, to what happens during surgery, to the daily reality of immunosuppression-isn’t just helpful. It’s essential.

Not everyone with liver disease gets on the transplant list. The decision is made after months of evaluation, not just by a doctor’s opinion, but by a full team: hepatologists, social workers, psychiatrists, addiction specialists, and financial coordinators. The goal? To make sure you’re physically ready, mentally prepared, and have the support system to survive the process.

The main tool used to prioritize patients is the MELD score-Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, INR, and creatinine. Scores range from 6 (mild) to 40 (critically ill). Higher scores mean higher priority. But it’s not just about numbers. If you have liver cancer, you must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors all under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level is over 1,000 and doesn’t drop after treatment, you’re typically ineligible unless you go through a special review.

There are hard stops, too. Active drug or alcohol use? You’re off the list. Metastatic cancer? No. Severe heart or lung disease that can’t be fixed first? Also no. Even if your liver is failing, other organs must be stable enough to handle the surgery.

And then there’s the psychosocial side. Do you have a place to live? Reliable transportation? Someone to help you take meds every day? Many centers require at least 6 months of sobriety for those with alcohol-related liver disease. But that rule isn’t the same everywhere. Some centers are now accepting 3 months with strong support systems, based on recent data showing similar survival rates. The inconsistency frustrates patients-and it’s one reason why some people wait years while others get a liver in months.

A liver transplant isn’t a quick procedure. It takes between 6 and 12 hours, depending on how scarred or damaged the old liver is. The most common technique used today is called the “piggyback” method. Instead of removing the entire inferior vena cava (the big vein that carries blood back to the heart), surgeons keep it intact and attach the new liver to it. This reduces blood loss and speeds recovery. About 85% of transplants use this method.

The surgery has three phases. First, the diseased liver is removed-this is called hepatectomy. Then comes the anhepatic phase: you have no liver at all. Your body survives on machines that keep blood flowing and oxygen moving. This part is risky. The longer it lasts, the higher the chance of complications. Finally, the donor liver is stitched in. Blood vessels and bile ducts are reconnected. The whole thing is like rebuilding a house while the occupants are still inside.

Most transplants use livers from deceased donors. But living donor transplants are growing. In this version, a healthy person donates part of their liver-usually the right lobe (55-70%) for adults or the left segment for children. The liver regenerates in both donor and recipient. Donors are typically between 18 and 55, with a BMI under 30. They must be free of liver, heart, kidney, or lung disease, and not use tobacco or alcohol. The remnant liver left in the donor must be at least 35% to ensure safety. The donor’s recovery takes 6 to 8 weeks. There’s a small risk: about 0.2% of donors die, and 20-30% have complications like infection or bile leaks.

One major advancement is the use of machine perfusion for livers from donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors. These are organs from people whose hearts stopped, not those who died from brain death. DCD livers used to have higher rates of bile duct problems. But with machine perfusion-where the liver is kept alive and monitored outside the body-complications have dropped from 25% to as low as 18%. The FDA approved the first portable perfusion device in 2023, extending how long a liver can be preserved from 12 to 24 hours. That’s a game-changer for matching donors and recipients across long distances.

The liver is a stubborn organ. It doesn’t like foreign tissue. That’s why, after transplant, you need drugs to suppress your immune system. Without them, your body will attack the new liver-and you’ll lose it.

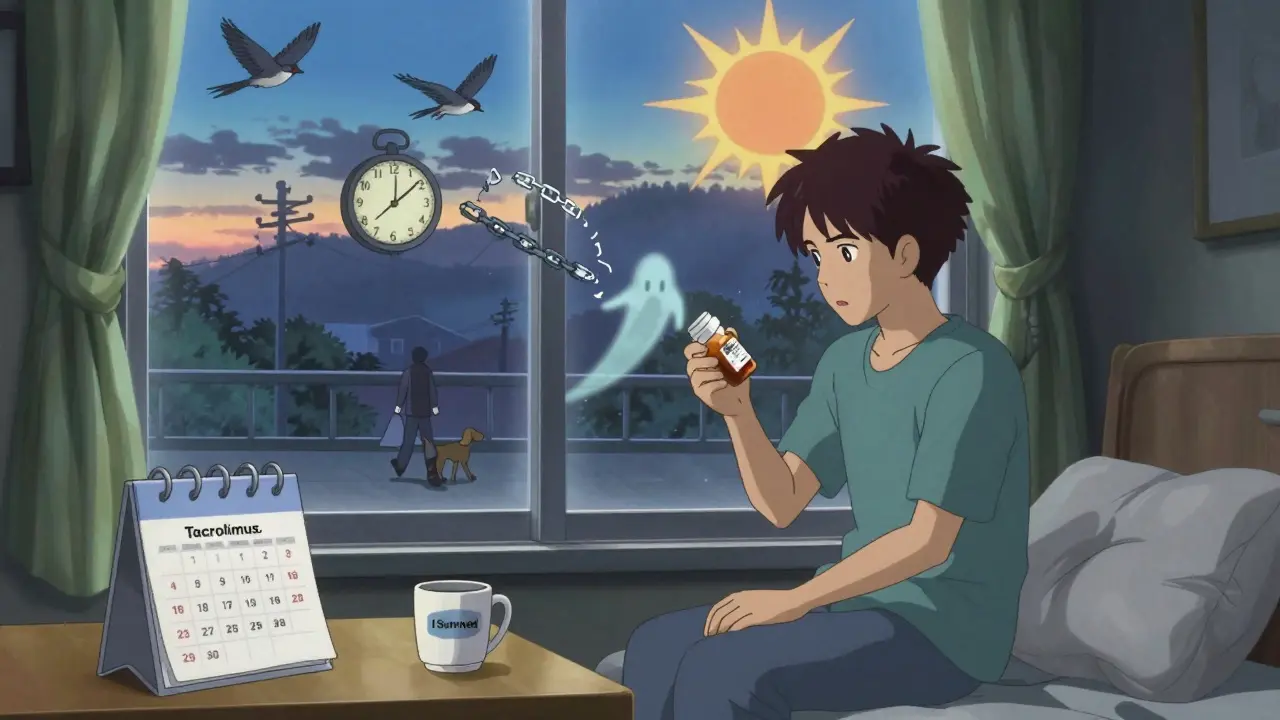

Most patients start with a combination of three drugs: tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. It’s taken twice a day, and blood levels are monitored closely. In the first year, doctors aim for 5-10 ng/mL. After that, they lower it to 4-8 ng/mL to reduce side effects. Mycophenolate prevents cell growth that leads to rejection. Prednisone, a steroid, is used early on but is often tapered off by 3 months.

Here’s something new: 45% of U.S. transplant centers now use steroid-sparing protocols. They drop prednisone after the first month. Why? Because steroids cause diabetes, weight gain, bone loss, and mood swings. Studies show this cuts the risk of new-onset diabetes from 28% to 17%. That’s huge.

But immunosuppression isn’t free. It comes with costs. Tacrolimus can damage kidneys in 35% of patients by year 5. It can cause tremors, headaches, and high blood pressure. Mycophenolate often causes nausea, diarrhea, and lowers white blood cell counts. About 15% of patients have an acute rejection episode in the first year. Most are caught early with blood tests and treated by adjusting doses or adding sirolimus.

Long-term, you’ll need blood tests every few months. The first year, you’ll go in weekly, then biweekly, then monthly. After year one, quarterly checks are typical. Medication costs average $25,000 to $30,000 per year-just for the drugs. Insurance often covers most of it, but not always. About 32% of transplant candidates report being denied coverage for pre-transplant evaluations. That’s a real barrier.

Choosing between a living donor and a deceased donor isn’t just about preference-it’s about timing and risk.

With a deceased donor, you wait. In some parts of the U.S., like California (Region 9), patients with MELD scores of 25-30 wait an average of 18 months. In the Midwest (Region 2), the same patient waits just 8 months. That’s a 10-month difference. Why? It’s not about how many donors there are. It’s about how organs are allocated. The system tries to prioritize the sickest, but geography still matters.

Living donor transplants cut that wait to about 3 months. But they come with their own risks. Donors face surgery, recovery, and long-term uncertainty. There’s also the emotional weight: giving part of your body to someone you love. Some centers now allow donors up to age 60 or BMI 32, based on new data showing safety. One 58-year-old donor in 2023 was approved because his liver anatomy was unusually favorable. That’s not common-but it’s happening.

DCD livers (from donors after heart death) are becoming more common. They made up 12% of all transplants in 2022. While they used to have higher complication rates, machine perfusion has closed that gap. Five-year survival for DCD livers is now 68%, nearly matching the 72% for brain-dead donors.

You’re not “cured” after transplant. You’re managed. Daily life revolves around pills, appointments, and vigilance.

You must take your meds at the same time every day. Miss one dose, and rejection risk jumps. Studies show you need 95%+ compliance to avoid rejection. That means no skipping pills because you’re tired, busy, or feeling fine. You’ll learn to recognize rejection signs: fever over 100.4°F, yellowing skin, dark urine, extreme fatigue, or abdominal swelling. If you notice any, you call your team immediately.

Infection is another big threat. Your immune system is turned down. A cold can turn into pneumonia. A cut can turn into sepsis. You’ll need vaccines (flu, pneumonia, hepatitis A/B), avoid raw seafood, and be cautious around pets and gardens.

And then there’s the emotional toll. Depression, anxiety, and PTSD are common. A patient in California told Healthgrades, “The transplant team’s social worker helped me get housing and bus passes. Without that, I wouldn’t have made it.” That kind of support isn’t optional-it’s part of the treatment.

Success rates are strong: 85% survive one year. 70% make it five years. Some live 20, 30, even 40 years after transplant. But it’s not guaranteed. It depends on how well you follow the plan.

The field is changing fast. Researchers are testing ways to make patients immune-tolerant-so they don’t need drugs at all. The University of Chicago has successfully weaned 25% of pediatric transplant recipients off immunosuppression using regulatory T-cell therapy. That’s still experimental, but it’s real progress.

Artificial liver devices? They help people stay alive while waiting-but none can replace a transplant long-term. The International Liver Congress says no device has kept a patient alive more than 30 days without a transplant.

And equity is becoming a focus. In British Columbia, new policies now include cultural support for Indigenous patients, adjusting abstinence rules to fit community values. That’s not just fair-it’s smarter. Treatment works better when it fits the person.

One thing won’t change: liver transplantation is still the only cure. No pill, no machine, no diet can fully replace a failed liver. But with better matching, smarter drugs, and more compassionate care, the future of transplant is brighter than ever.

Yes-but only after a mandatory period of sobriety, usually 6 months. Some centers now accept 3 months if you have strong support and show commitment to change. Each transplant center sets its own rules, so it’s important to discuss your history openly with your team. Abstinence isn’t just about the liver-it’s about your ability to follow complex medical care long-term.

It varies widely. In the U.S., waiting times range from 3 months to over 2 years. Your MELD score is the biggest factor-higher scores get priority. Geography matters too: patients in the Midwest often wait less than those on the West Coast. Living donor transplants can eliminate the wait entirely, but not everyone qualifies or has a willing donor.

The top risks are rejection, infection, and side effects from immunosuppressants. Rejection happens in about 15% of patients in the first year. Infections-like pneumonia, urinary tract infections, or even common colds-can become serious because your immune system is suppressed. Long-term, drugs like tacrolimus can damage kidneys, cause diabetes, or lead to nerve problems. Regular monitoring and strict medication adherence reduce these risks significantly.

Yes, many women have healthy pregnancies after liver transplant. But it’s not simple. Doctors usually recommend waiting at least 1-2 years after transplant to ensure stability. Medications may need to be adjusted-some immunosuppressants are safer than others during pregnancy. Close monitoring by a high-risk OB team and your transplant doctor is essential. Success rates are good, with over 80% of pregnancies resulting in healthy babies when managed properly.

Most insurance plans, including Medicare and Medicaid, cover liver transplants. But pre-approval is required, and not all costs are covered. Some centers report that 32% of candidates face denials for pre-transplant evaluations, which can delay or block the process. It’s critical to work with a transplant financial counselor to understand your coverage, appeal denials, and explore assistance programs.

Thank you for this incredibly thorough breakdown. As someone who works in healthcare policy in Ireland, I’ve seen how inconsistent transplant criteria can be across regions. The MELD score is a necessary tool, but it’s not the whole story. What truly matters is the ecosystem of care surrounding the patient-housing, transportation, mental health support. These are the invisible pillars of transplant success. I hope more systems adopt the holistic model seen in some Canadian and UK centers.

Let’s be real-people who drank themselves into liver failure don’t deserve a new one. It’s not rocket science. You made your bed, now lie in it. Why should a perfectly healthy donor organ go to someone who chose alcohol over their own life? I’ve got a cousin who died waiting because some drunk got priority. This isn’t charity-it’s a moral crisis. Stop pretending sobriety timelines are ‘flexible.’ They’re not. It’s called accountability.

OMG this is so helpful!! I’ve been researching for my dad and this cleared up SO much 😊 The living donor part? Mind blown. I had no idea the liver regenerates!! And steroid-sparing protocols?? YES PLEASE. My aunt went through prednisone hell-weight gain, mood swings, the whole deal. If we can skip that, sign me up!! Also-machine perfusion?? That’s like sci-fi becoming real lol. Thank you for breaking this down in a way that doesn’t make me wanna cry 😭

Here’s the raw truth nobody’s saying: the transplant system is a rigged game of socioeconomic roulette. If you’re white, middle-class, and have a family member with a pulse who can drive you to appointments? You’re golden. If you’re Black, Indigenous, or poor? You’re stuck in bureaucratic purgatory. The 6-month sobriety rule? It’s a gatekeeping tactic disguised as ‘safety.’ Meanwhile, rich folks in Florida get transplants in 90 days while folks in Appalachia wait two years. And don’t even get me started on insurance denials-32%? That’s not a statistic, that’s a crime. The system isn’t broken. It was designed this way.

This was really well written. I’m a nurse who’s seen a lot of transplant patients, and the emotional toll is just as heavy as the physical one. The meds, the fear, the guilt-especially if they had a living donor. I’ve had patients cry because they feel like they’re ‘using up’ someone else’s body. No one talks about that enough. Thank you for including the psychosocial side.

I’ve been mentoring families through the transplant process for over a decade. One thing I always stress: it’s not about being ‘worthy.’ It’s about being prepared. The real miracle isn’t the surgery-it’s the daily discipline of taking pills at 7 a.m. and 7 p.m., every single day, for the rest of your life. That’s the invisible labor of survival. And if you have someone who reminds you, checks in, holds your hand during blood draws? That’s the secret sauce. We need more of that-not more rules.

So many lies in this article! In India we have the best liver transplant centers in the world! We do 10,000+ transplants a year! Why do you think they are so expensive? Because we are the best! The west is so slow with their rules! 6 months sobriety? Pfft! In Mumbai we do transplants after 1 month if the family is supportive! And guess what? Our survival rates are higher! Because we believe in family! In India we don't wait for machines or perfusion! We use the power of love and tradition! Also I think you should be more proud of your own country's system instead of praising foreign tech! We have AI liver analysis now! Just not in your country because you are too slow! I am so proud of Indian medicine!

Just wanted to add something about DCD livers-this is huge. I’m a transplant coordinator in Melbourne, and we’ve gone from 22% bile duct complications in DCD grafts to under 15% since we started using portable perfusion. The real game-changer? It lets us shuttle livers across states without rushing. We had one liver go from Tasmania to Perth, preserved for 21 hours, and it’s still functioning perfectly 3 years later. That’s not just innovation-that’s equity. It means people in rural areas aren’t left behind just because they’re far from a major city. We’re finally fixing geography, not just biology.