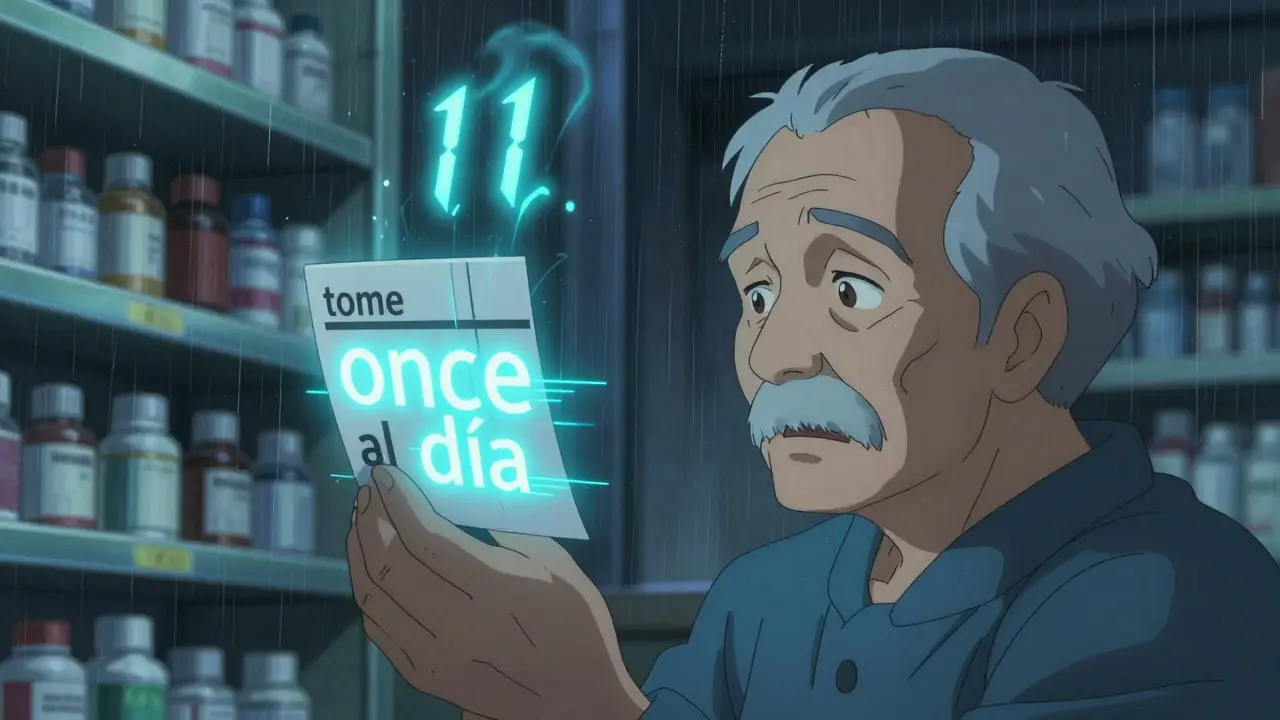

Imagine taking your medicine because the label says once a day-but it actually meant eleven times a day. That’s not a horror story. It’s what happens when pharmacy labels are translated by machines without human oversight. In the U.S., millions of people rely on translated prescription labels just to take their meds safely. But too often, those translations are wrong-and the consequences can be deadly.

The word "once" in English means "one time," but in Spanish, "once" is also the number 11. Automated translation systems don’t understand context. They pick the most common translation without checking if it makes sense medically. So a label saying "take once a day" gets translated as "tome once al día," which a Spanish speaker might read as "take eleven times a day." This is one of the most dangerous translation errors in pharmacy labels.

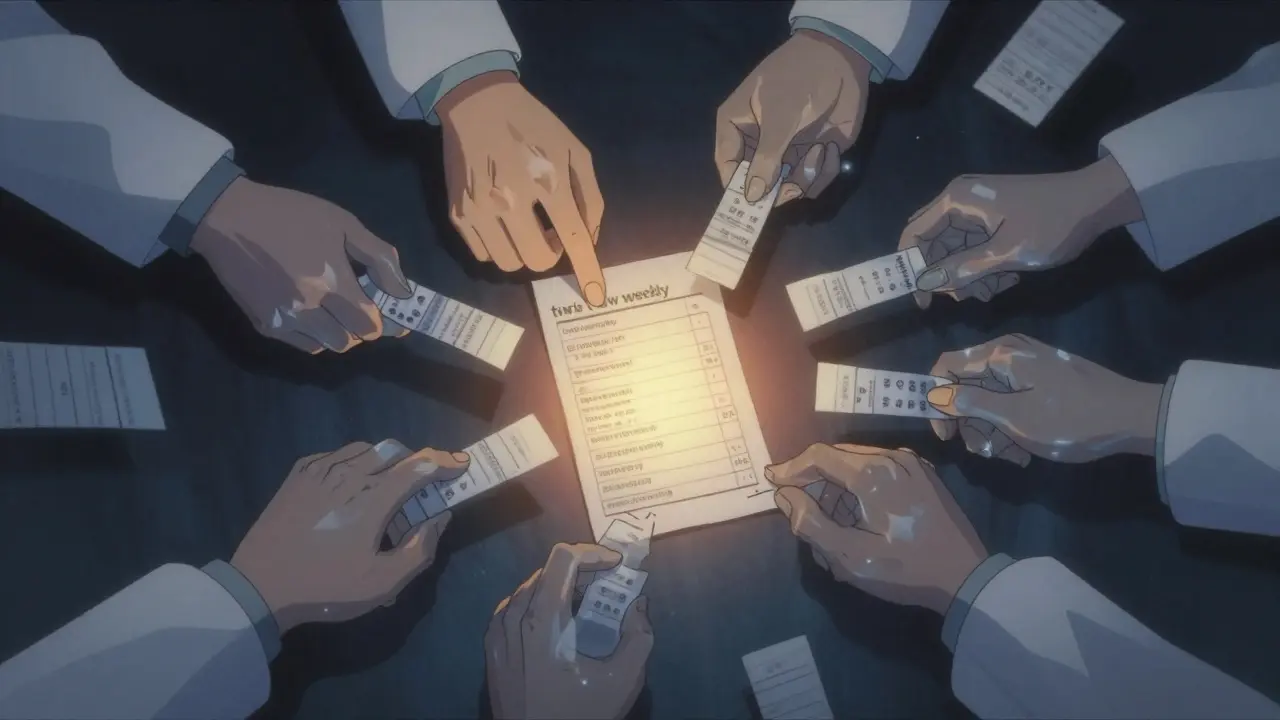

As of 2026, only California and New York have state laws requiring accurate, human-reviewed translations on prescription labels. California’s law (SB 853) took effect in 2016 and requires labels in Spanish, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean if those languages are spoken by 5% or more of the local population. New York’s Local Law 30 of 2010 requires translations for Spanish, Chinese, and Russian in certain areas. Other states have no such requirements, though many are considering similar laws.

Yes, and you should. You have the right under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act to receive language assistance in healthcare. Call ahead and ask if they use certified medical translators. If they only use machines, ask them to order a professional translation. Most pharmacies can get one within 24 hours at no extra cost to you. If they refuse, file a complaint with your state’s board of pharmacy or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Yes, but only when combined with human review. AI tools like Walgreens’ MedTranslate and CVS’s LanguageBridge can catch 60-70% of errors by flagging bad translations. But they still need a pharmacist or certified medical translator to verify the final version. Pure AI translation without human oversight still has error rates over 50%. The best systems use AI to speed up the process, then add a human check before the label is printed.

Call your doctor or pharmacist immediately. If you’re having symptoms like dizziness, nausea, rapid heartbeat, or confusion, go to the nearest emergency room. Don’t wait. Then report the label error to the pharmacy and your state’s board of pharmacy. Keep the label as evidence. You’re not just protecting yourself-you’re helping prevent this from happening to someone else.

No. Under federal law, healthcare providers-including pharmacies-must provide language assistance at no cost to patients with limited English proficiency. You should never be charged for a certified translation of your prescription label. If a pharmacy tries to charge you, ask to speak to a manager and mention Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. If they still refuse, file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

So you’re telling me my abuela’s pills could kill her because a computer thought "once" meant 11? And we’re still okay with this? I mean, we have AI that can write sonnets but can’t tell the difference between a number and a word? That’s not a tech failure. That’s a moral one.

Let me get this straight - we spend billions on Mars rovers but can’t afford a human who knows Spanish? The machine didn’t fail. We did. We chose cheap over safe. We chose convenience over life. And now we act surprised when someone dies because a label said "once" and meant "eleven"? That’s not a translation error. That’s negligence dressed up as innovation.

And don’t give me the "it’s just one word" line. One word killed a kid in Ohio last year. One word. That’s all it took. We treat language like a commodity. It’s not. It’s a lifeline.

Meanwhile, the FDA recommends certified translators. But only two states enforce it. The rest? Guess what. You’re playing Russian roulette with your insulin.

And don’t even get me started on the "AI fixes it" hype. AI doesn’t understand context. It understands patterns. And patterns don’t care if you’re diabetic or dying. It just spits out the most common match. That’s not intelligence. That’s laziness with a PhD.

We need a cultural shift. Not a software patch. We need to stop treating non-English speakers like an afterthought. They’re not a demographic. They’re people. With families. With fears. With medicine that could kill them because a bot thought "once" was just a number.

The ontological dissonance here is pathological. Automated linguistic mapping without semantic grounding in pharmacological pragmatics constitutes a systemic epistemic failure. The lexical ambiguity of "once" - a homograph with cardinal and adverbial valences - is not a technical glitch but a symptomatic manifestation of epistemic violence against LEP populations.

When machine translation substitutes syntactic probability for semantic fidelity, it enacts a form of linguistic colonialism. The pharmacy’s algorithm privileges Anglophone lexical dominance, rendering non-English speakers vulnerable to iatrogenic harm through structural misalignment.

Moreover, the regulatory lacuna in 48 U.S. jurisdictions reflects a bioethical deficit. Title VI mandates equitable access, yet compliance is treated as discretionary. This is not negligence. It is institutionalized harm.

The 63% error reduction in Walgreens’ pilot is statistically significant (p < 0.01), yet still leaves 37% of translations unvetted. That’s not progress. That’s a death sentence with a barcode.

I’ve worked in community pharmacies for 18 years. I’ve seen this happen. A woman came in once, shaking, saying her blood sugar dropped to 38. She thought "take once daily" meant "take eleven times daily" because the label said "once" in Spanish. She didn’t know the word "once" could mean eleven.

We called her doctor. She ended up in the ER. She cried the whole time. Not because she was scared - because she felt stupid. Like it was her fault.

It wasn’t. It was ours. We’re the ones who let machines do this. We’re the ones who didn’t push harder. We’re the ones who said "it’s too expensive" instead of "it’s too dangerous."

And here’s the thing - you don’t need fancy AI. You just need one person who knows both languages and knows medicine. That’s it. One person. That’s all it takes to save a life.

Call your pharmacy. Ask if they have a certified translator on staff. If they say no, ask why. Then ask again. And again. Because if you don’t, who will?

Man, this hits different when you’ve seen your uncle nearly OD because his label said "twice weekly" but meant "twice daily." We’re not talking about grammar here. We’re talking about survival. And it’s wild how fast we normalize this stuff.

Like, yeah, AI’s cool. But if your AI can’t tell the difference between "take with food" and "take after food," maybe it shouldn’t be translating your grandma’s heart pills.

And don’t get me started on the "Spanglish" labels. One pharmacy in my town says "tomar una pastilla cada dia para presion alta" - clean, clear. Another says "take 1 pill daily for high blood pressure" - what the actual hell? Why mix languages? Are they trying to confuse us or just lazy?

Bottom line: if you’re a pharmacy and you’re still using machine-only translation, you’re not a healthcare provider. You’re a liability with a receipt printer.

And if you’re reading this and you’re not sure what your label says? Don’t guess. Call your doctor. Ask for a printed copy. Demand a human. You’ve got rights. Use them.

I read this and cried. Just… cried. My mom died because of this.

So let me get this straight - you’re blaming the machines? The real problem is that people can’t learn English. Why should pharmacies pay for translators when immigrants can just… learn the language? It’s not that hard.

AI-driven NLP pipelines with intent-aware disambiguation modules can reduce lexical ambiguity by up to 72% when fine-tuned on pharmacologically annotated corpora. The real bottleneck isn’t tech - it’s regulatory inertia and reimbursement models that disincentivize human-in-the-loop verification.

Current FDA guidelines are aspirational, not enforceable. Without mandatory certification requirements tied to Medicaid/Medicare reimbursement, pharmacies will continue to optimize for cost, not clinical safety.

Neural machine translation + human adjudication is the gold standard - but only if the adjudicator is board-certified in medical translation. Not just bilingual. Not just "fluent." Certified. With continuing education. That’s the missing piece.

You know what’s wild? We’ve got apps that can translate menus, signs, even street signs in real time. But when it comes to your life - your medicine - we hand you a printout from a bot that thinks "once" is just a number?

This isn’t about language. It’s about dignity. It’s about saying, "You matter enough to be understood."

And here’s the thing - you don’t need to wait for the government or the pharmacy chain to fix this. You can start today. Walk into your pharmacy. Ask for a human translator. If they say no, ask again. Then ask your doctor. Then your insurance. Then your state rep.

Change doesn’t start with a law. It starts with one person refusing to accept "it’s just how it is."

You’re not asking for special treatment. You’re asking for basic human decency. And that? That’s never too much to ask.